Why Silent Cartoon Zig and Sharko Offers the Perfect Writing Exercise

From time to time, I like to indulge in bad TV like Mechagodzilla or Xena: Warrior Princess. Those kinds of shows let me zone out for a while, and their absurdity serves as a counterweight to the seriousness that most of the rest of my life has.

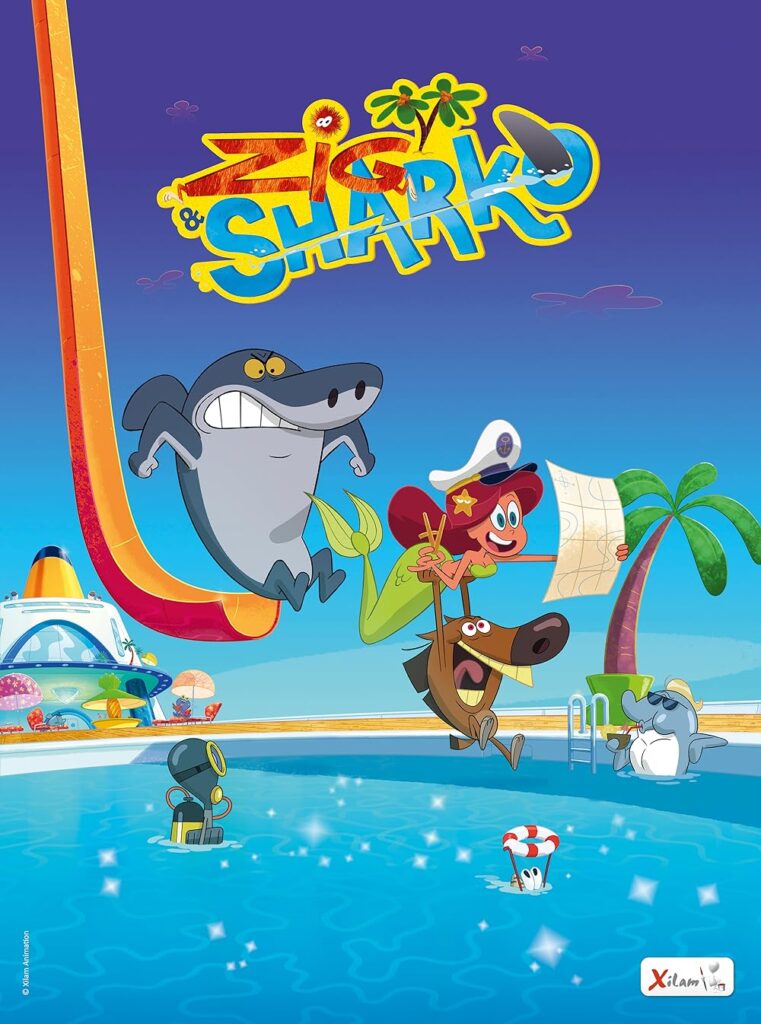

Yet, as a writer, I can’t turn off the part of my brain that analyzes the imagined process of the shows. I think about what goes on in the writer room and the conversations that go on between staff members. Lately, I’ve found myself focusing on Zig and Sharko, a comedic, slapstick kid’s cartoon featuring a mermaid (Marina), her best friend and protector (Sharko), Zig (the hyena who’s constantly trying to eat Marina), and Bernie the crab (Zig’s friend and accomplice).

What sets Zig and Sharko apart

Part of the reason I adore this show is because there is absolutely no dialogue. From that perspective, it’s in the vein of and draws inspiration from the classic Road Runner cartoon, pulling on this-will-be-in-every-episode concepts. The fact it’s a silent cartoon makes it an outlier in kid TV, but it works for the same reasons Road Runner did.

How to use the cartoon as a writing exercise

Watching the show is a great exercise for writers, who can consider how animators communicate plot and character responses. It encourages a degree of mental storyboarding and visualization that many writers don’t do.

What would happen to your own scene or chapter if you eliminated the dialogue as a mode of critique?

- Can you suddenly see where showing an action or emotion is important?

- Is it easier to think about the characters’ environment and how the characters move through it?

- Is the interaction between your characters reasonable for their development?

- Do you notice any ticks you’ve been leaning on for what characters do or how you describe the environment?

- Where might you be relying on dialogue in the scene or chapter too heavily?

Books and film often connect, with stories being made into TV shows or movies after publication. I’ve written previously on how viewing stories as film can aid the creative writing process. But in Zig and Sharko, there’s a specific opportunity to focus on the balance between dialogue and the action/environment you ask readers to visualize.

Once you’ve run through your content with a Zig and Sharko analysis, consider flipping the process. What happens if everything is dialogue? Thinking of the scene or chapter that way might help you figure out what lines to cut or intensify, since there’s no way to let the characters use the environment to speak to the reader.