Why I Hated ‘Bridgerton’ on Netflix

During the pandemic, like so many others who are trying to navigate life with lockdown restrictions, I turned to Netflix. And because I have an affinity for period books and films (minus the uncomfortable stupidity of corsets, of course), I thought Netflix’s Bridgerton would be a good choice.

Did I binge-watch the first season?

Yes.

Did I enjoy it?

Not so much.

I realize that, in this opinion, I’m perhaps an outlier. In an article for Bloomberg, for example, Martin Ivens gushed over the series for its escapism, dramatic impact, rich costuming, and diverse casting. It proved, Ivens wrote, that “as long as audiences are entertained, they will welcome innovation, too.”

But I am hardly alone.

Artistic license cannot dissolve respect

The first reason I feel annoyed at Bridgerton is simply that it takes such license with Julia Quinn’s books.

I am not opposed entirely to the idea of creative shifts in productions. I did lots of theater and I understand that artistic interpretation has value. There also are lots of examples where an interpretation helped a work resonate with audiences. I get that showing current relevancy ensures that any art doesn’t die.

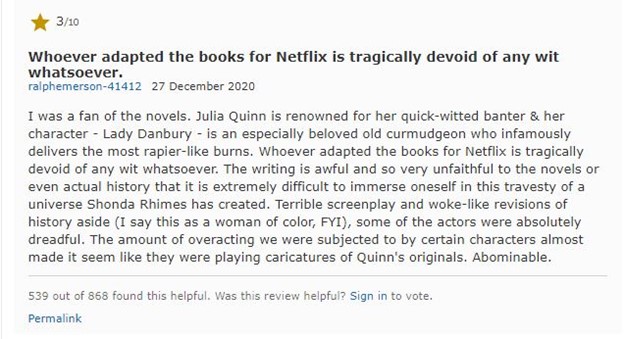

But when that interpretation entirely changes the core elements of a work, I question it. Quality of the acting aside, as one reviewer on IMDB put it:

As a writer, I wouldn’t expect a producer to take one of my books from page to film without a tweak here or there. But I would want them to respect the work I put my heart and soul into enough to at least maintain characterizations and portray the bulk of my world as I had envisioned it. Because if the goal is escapism, juxtaposing issues from this world on top of the fictitious one that’s meant to be different, even with the positive intent of showing us how we might make our world better, bursts the bubble. Instead of being transported in our minds to an entirely new place, we stay chained to the realities of where we are and are forced to swallow them. We never truly get free.

Adaptation does not mean that you entirely throw away the original creativity or vision just because you want to explore or stress cultural points. Don’t supercede or destroy the author’s original intent and voice just because you have your own message.

So in this sense, I just can’t give Bridgerton too many points.

*deep breath*

But how did they talk, though?

The second reason I ended up cringing is the script.

Anyone who has read any modern romance novels understands that the genre has all kinds of linguistical and plot-based tropes. “Creamy white thigh”, for example. “Strong line of his jaw” and “heaving bosom” are two other favorites that I good-naturedly laugh at.

But while a period romance might gush about touch and describe the feeling or action of it in all manner of ways, it’s a rarity for a character to come right out and say something so blunt like “You can touch yourself” (a much-quoted line from the duke). Half the fun of a “trashy” romance is the poetic way they convey a concept without being blunt, the way they find a way to say what everybody aches for them to say without actually using “improper” or “impolite” phrasing. This isn’t to say characters wouldn’t talk face-to-face about things like sex as their passions get hotter. But I would have loved to see more eloquence as things got steamy. Caressing diamonds, for instance, might have nothing at all to do with fine jewels.

And this to me is the glaring irritation that blinds me. So many times when I was watching, I could not get past the feeling as though all the flowers of 1800s language had wilted, replaced with lazy modern expressions. Sure, you can find lots of analogies. But the Bridgerton dialogue didn’t cut, the romance didn’t sizzle, and the characters didn’t seem as individual as they might have, because the way those analogies were put to the screen had such little rhythm or specific connotation.

Does including those nuances mean that the characters might sometimes have to use more words? Yep. And you do have to take that into account when working on scene pacing. But I would argue that any increase in verbosity is worth the added flavor and the ability to better see who is on the page and where/how they live and think.

In summary…

- Dismantling and interpreting someone else’s work are two different things. You don’t have to stick to the original to the letter, but there shouldn’t be a question of what the original is like overall, and the new world should let us be free from the real one.

- How you say something is just as important as the base concept. Don’t be lazy. Offer the nuance, even if it takes a little more carefully distributed ink.

Now to scroll through my Netflix options and find something else…