The National Archives Needs Cursive Readers, and Now I’m Depressed

Can you read cursive handwriting?

Many people can’t now — teaching this form of penmanship has been dropped in many areas of the country, with only 24 out of the 50 states requiring schools to teach it.

But is the shortage of people who can work with the style such a dying art that the National Archives would ask for volunteers specifically to read documents originally created in cursive?

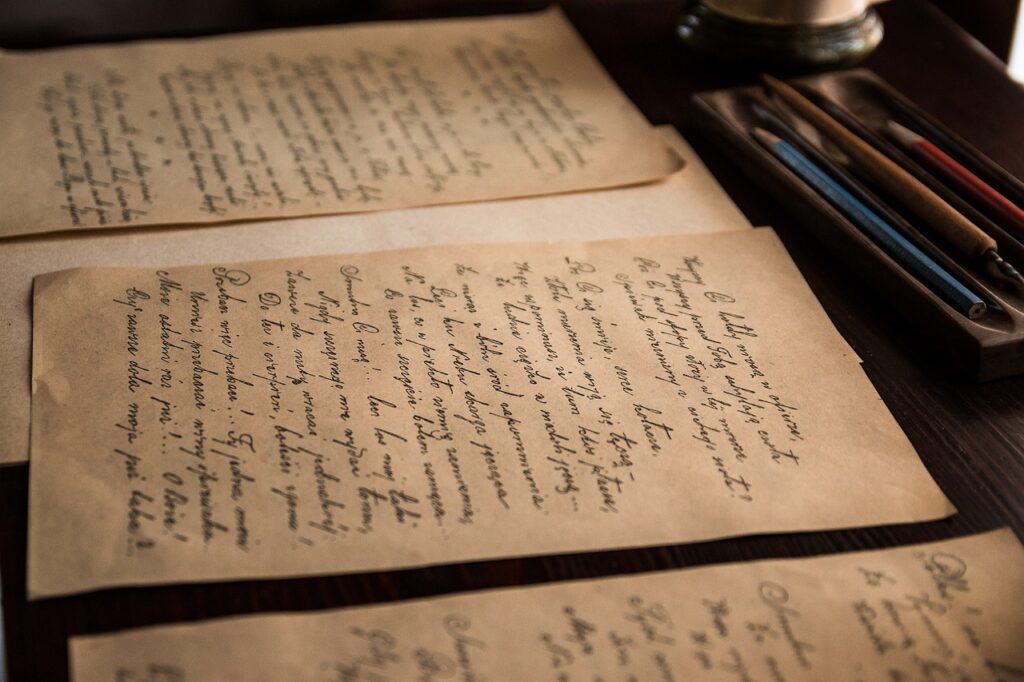

Apparently so. The documents the National Archives wants help with are mainly from the Revolutionary War era. During that time, cursive was the standard.

As I read articles about the organization’s request, I had a startling revelation that I am one of the last generations where that standard still applied.

It made me sad.

In penmanship, opportunities

My sadness wasn’t because I felt old, although I admittedly did (I’m currently 42 as I write this). It was because I thought how so many people won’t know the satisfaction of physically creating words. There’s something miraculous and healing in that, each connected movement of the pen building something sensible and intimate out of nothing. It’s therapeutic to shift across the paper with a rhythm all your own, and I want people to understand and experience that.

Then there’s the scientific fact that physically writing something is better for memory than typing. Ever since high school, I would take good notes. I would barely look at them again. But I would remember what I wrote. Even now, it is easy for me to remember short segments I’ve penned and rewrite them again if needed. I don’t want people to deny themselves the convenience and enjoyment of that recall.

I remember, too, being deliberate in shaping the appearance of my script. Some degree of penmanship is simply what you’ve got, your motor control and even the size of your hands. Handwriting also connects to everything you feel — what you write when you’re upset isn’t going to look exactly the same as what you write when you are calm or happy. So, there are some limitations to what you can make it.

But there is some sense in the idea that people can direct who they are through intentional choices. And I wanted (and still want) my handwriting to send a message — to myself and others — that I held a graceful power. Although I’m not sure I got that effect I wanted, I still worked hard to make every letter my own. As a result, my cursive is not true cursive anymore. Instead, it’s a bit of a hodgepodge. It flows in some spots and disconnects in others, yet the shape and evenness of it is, to my mind, still artistic and aesthetic. So, it’s depressing to me to think that so many others won’t see the evolution of who they are or what they feel on the page.

Language is not static, nor are the tools we use to apply it. This is not the first time that something about the way we communicate has fallen away. But as it does, I sit in gratitude for the experience I have had and the fact I took some pleasure in it. There might yet be some hope in the preservation that sometimes happens with nostalgia — perhaps, in the same way some people collect vintage records or old video games, there will be those who hang on to this way of writing, simply because they can see its beauty and what the experience offers. I’ll make sure to keep some pens at the ready, just in case.